I had heard of Alexander Movement a long time ago and wondered if it had any commonalities to Bohm’s Artamovement.

No, no correlation – David Bohm didn’t know or study Alexander Technique. He should have, because it would have helped him with depression. AT also specialized in the study of proprioception, which Bohm loved to discuss. Any similarity comes from both minds studying human nature and seeing similar characteristics in operation. Great minds think alike!

it was interesting that when you spoke of the “non-absolute characteristic of our ability to recognize sensory differences”, this seemed almost like what I call error. To me, absolute truth is also of little importance. That’s because I think we can know when things err from expectations or from desired ends (negative knowledge) even when we can’t know > anything positive about a situation. This sounds to me like your “recognizing differences.” Erring seems to me almost a synonym for “differing”, for it originally meant something like “moving away”, “straying.”

It’s not “error,” or at least I don’t think of it as error. It’s a built-in characteristic of the way humans are built to register differences and to adapt to circumstances. Brilliant design, actually, but any design has limitations. I see that you seem to have glorified “error,” but I think that’s the long way around and it is slightly confusing.

Paradoxes, I believe, are what we should seek. “Should” in the sense that it’s fun to find them. They reveal all kinds of “differences”, errors, in the movement of thought. The paradox of choice, for instance, reveals to me the sense of personal agency on one hand — my autonomy seems represented in the fact that I “make” decisions. But on the other hand, there is the sense that when an insight occurs for the first time, it occurs without “me” being engaged (again, depending on our definitions of “me” and “engagement.”). It can get very confusing very fast. But I think the facts, the truth, the actuality, sometimes busts in on my assumptions and rearrange them against my will even. Often, my discoveries of error are certainly not discoveries I’d have chosen. I sometimes resist them to the last minute.

Yes – a paradox is what emerges when you are learning and what you expected isn’t happening to plan! The way I like to describe it is that insight comes from the unknown, after the habits stop insisting things “are” certainly familiar old same things and there is no necessity for anything new to intervene and rock the status quo. Habit seems to insist on its own usefulness and ultimate importance – quite an overwhelming resistance, depending on the investment someone had to put out to install and use a particular habit. It’s a story of what someone does when confronted with the obvious discovery that they are mistaken, made an error or didn’t know it all – as you point out.

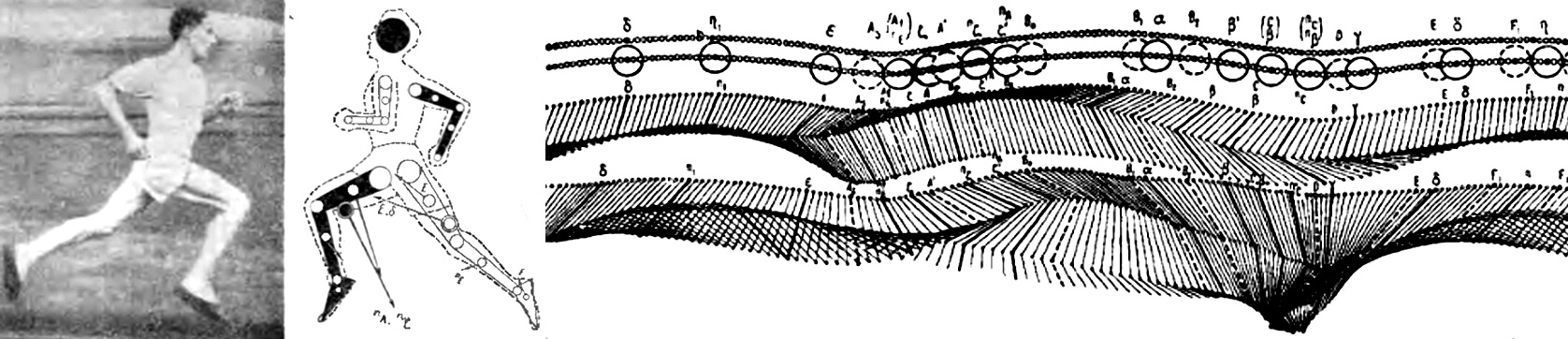

For instance, I believe I’m moving mindfully, but the fact is I constantly bump into one thing or another. The bump is actuality, is error, is perhaps a “sensory difference.” It might signify to me directly that I’m moving without mindfulness. And this very perception is a moment of proprioception, of seeing that my typical reaction — “Yes, of course I know how to move correctly, don’t be so foolish!” — was only a reflex assumption, and wrong to boot.

Well, we don’t know everything, and we’re not responsible for everything that occurs – it’s a childish notion that because things matter to us and are so constantly referenced to the self, that YOU are in charge of everything that happens. Shit happens, people grow up and circumstances change and we must get used to wielding bodies of a different shape and size, for instance – then we have to figure out how we are going to respond once we find ourselves in the circumstances at hand. A friend of mine once expressed this in the quote: “The only thing we HAVE to do is die. There’s always another choice.” Another example of that was noticing my stress level going up after having been traveling for two months. I decided when traveling in other countries, the point of traveling was to get myself lost and then have a good time learning where I was located in space.

What you’ve continued explaining is fascinating! All this without knowing how similar A.T. is in examining and dealing with these ideas. The way I like to describe it, given my experience with A.T., is that a habit or routine buries it’s existence into an innate sense as its nature. That’s how habits are designed, so they can become second nature and relied on so you can add another habit on in a chain of skill building. As you “bump into” stuff you didn’t expect, it’s a signal that a habit or assumptions exists or that you don’t know everything. Rather than reinforcing the need for the habit (as you narrate the urge to do with a “reflex assumptions,”) now that you are reminded the routine exists, you can subtract it or suspend it to find out something new by paying special attention – if you are willing and ready at the time for something new to occur. Paying special attention is a skill that needs some practice in most people – but in you, it’s a pretty well-honed natural talent that has been shined up into a skill. A person’s original natural sensitivity to discern more subtle perceptual differences will re-emerge as well as an easier way, an insight or a discovery as you try out your ideas. What happens when you are experimenting may feel “weird” or “unfamiliar.” This is your “spontaneous perception” that you described. So many people dismiss this novelty as meaning nothing and pull themselves back into their familiar, (but stressed out,) habits and attitudes. (Attitude in the sense that some boats may sometimes sit in the water with a leaning attitude that must be constantly taken into account during navigation.) The habitual urge is quite strong and insistent. You are an amazing, rare and keenly observant person to have noticed and have been able to outline these characteristics of discovery by yourself.

And what do we choose? I think we choose the preconditions, not the actual insight. Yes, I think I can remove excess baggage from the ground — prepare the ground — for insight. I could learn what it means to sit quietly for instance, with a silent, alert mind. But there would have to be no effort in that, or even any conscious will. For will and effort ARE forms of thought, however subtle. Thought would have to stop, without “stopping” thought. It would have to be an action that isn’t “Mine”, therefore. Not the “mine” that I typically imagine as “me”, as the Chooser. So I tend to think that something choiceless has to happen in an insight.

In Alexander Technique, we call it “inhibition.” Essentially, the choice to prevent (to stop) habits from running the show and coerce all possible outcomes. What emerges as we stop the habit is a sense of “do-less-ness,” a feeling of lightness and effortlessness in our quality of motion that is a signature of the experience an AT teacher can show you.

Print your post out and give it to your teacher when you get around going for a lesson. The missing piece for you will merely be the discipline of how to bring these ideas as an example into your every movement, which AT can provide.

My long term experience in having used AT is that the “me” in this body of mine has become more of a fitting Director of the dance, so to speak, rather than a Dictator or insecure Reactor. Almost as if my artistic side that creates meaning has just as much influence as the talking, organizing side over my decisions that influence my life. The “I” in me knows that it is a fictitious name, in some way – that the “real” me is the choices I make. With the integration, the whole that is me, I am now somehow able to notice and connect the meanings of my smallest choices, accounting for time of arrival much more elegantly. In a sense, my choices, now made with more of the whole of myself being present in a sort of simultaneous state of all points awareness, the me that is I has become more artistic, more symbolic, more spiritual and more coherent in my expressions. Every moment counts now, because I’m able to be more “in the moment” and flit back into the more linguistic, articulate side that seems to want to run the show when I want to, rather than only having that one bag of tricks.