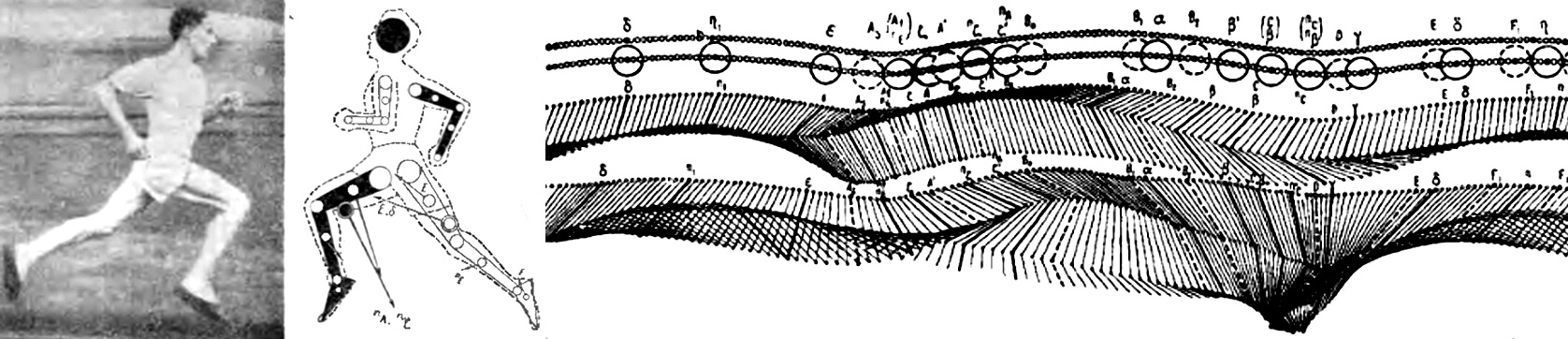

Strangely enough, awareness of bodily location improves during any motion – whereas stillness is propreceptively self-deceptive.

You can experiment to see this in action right now, (as long as you’re not driving a vehicle!)

You’re going to touch the middle of your finger to the exact middle of your nose – with your eyes closed and your head still. (Of course, your arm has to move…)

Then, while slowly moving your head from side to side while your eyes are still closed, repeat. Do your second attempt to touch the middle of the same finger to the middle of your nose…

How did the two attempts compare? Most people find the second attempt more successful, with the exact center of their finger being closer to the exact center of the end of their own nose. Did you? (You can redo the first attempt again also, to correct for practice being a factor.)

Generally, people’s capacity to judge bodily orientation and relative effort is tied to being in motion. Proof of this would having it be trickier to do the same experiment with your head still – than when your head was slowly moving. But – most people assume this experiment would be more difficult while moving.

The way you can use this in your daily life is whenever you want to compare the relative success of one example to another – probably during the practice or learning of a particular skill. Perhaps this tip would also be useful when you want to figure out if your chair is “comfortable” in a variety of possibilities?

The tip is to always do your “after” comparison sample AFTER you’ve been in motion. If you do a “before” sample, you’ll perceive your habits. Comparing when you’re not moving won’t work as well. Your sensory abilities won’t be receiving clear information from your capacity to judge relative effort and absolutely factual location of your body and limbs. Habits “hide” sensory capacity so effectively that sometimes we don’t even know we’re doing what we’re doing!