Rumor has it that kids don’t grasp abstract thought until they’re older. At a young age, the ability to do so is supposed to be undeveloped.

Grown-ups who are supposed to be capable of abstraction also seem to have trouble recognizing it is happening too. Trot out abstract art, for instance; many adults haven’t a clue how to decipher the intent of an abstract artist. Some of the secret questions to answer when looking at art is to imagine,”Why would someone do this?” “What state would a person need to maintain to do this?” But these questions are missing for most adults because they have been trained in school to answer questions and not formulate them.

But there’s another reason people aren’t commonly able to perceive abstract means. They get dazzled by “valuable” content. They’re so fixed on the content of what happened when they were experimenting or thinking creatively that they lightly skip over any awareness of what they did to get what they wanted. One of the most common questions students wonder about after an Alexander Technique teacher gives them a hands-on guided modeling turn is, “How did you do that to me?”

Meet my two young students. They are sisters, eight and ten years old. Their parents and Hula teacher want them to learn better posture. As their teacher, I imagined that the grammatical structure of language that mostly every kid masters before age three or four has got to be abstract enough to certify them being able to do so. These two kids double qualify as great students because they also speak Japanese flawlessly.

Imagine these kids to be sort of like an Artificial Intelligence that don’t have enough context to abstract yet. As their teacher, I have to figure out what that experience is and provide it for them. Abstract (in our case of learning Alexander Technique) means the underlying process, principles or events that are supposed to be inside the process of how the wanted result happened. They can’t use what I teach them unless they understand how to apply it.

So – what is the most important first-hand experience that these kids might be missing that I would commonly assume every adult already has?

I thought back to my stepson playing on a swing at four years old, discovering an amazing twist and whirl. Then when he got his dad’s attention, he was so disappointed that he couldn’t repeat his previous success for his dad to see him doing. Then I realized something: Kids only have trial and error to train themselves to learn something physical, and the likelihood of repeating a new success is tiny. No wonder learning a physical trick is so frustrating next to pushing buttons on a video game!

So that meant I first had to teach these kids how to train themselves.

For kids, (for all of us, really) any missing link of abstraction can be taught through storytelling. Kids need a context, and these contexts need to be built by example or illustration in ways they can identify with the characters in a story. In order to imagine a motive, you must be able to put yourself in a situation where that motive makes sense. If people are going to read minds and use what the brain science people call “mirror neurons,” they need some familiarity with situations that people experience. So how could I orchestrate a context for learning how to train?

I had one kid pretend they were a very smart animal and the other kid was the trainer. They used a clap for signaling successes – no talking. We had great fun training each other to do odd things. The kids also learned how to be clear, kind to themselves and use the important elements of training such as taking care with timing to reinforce the right behavior, preventing the animal from learning the wrong things and celebrating successes. Now when learning new skills, they understood that they were both the animal and the trainer. (Thanks to Karen Pryor.)

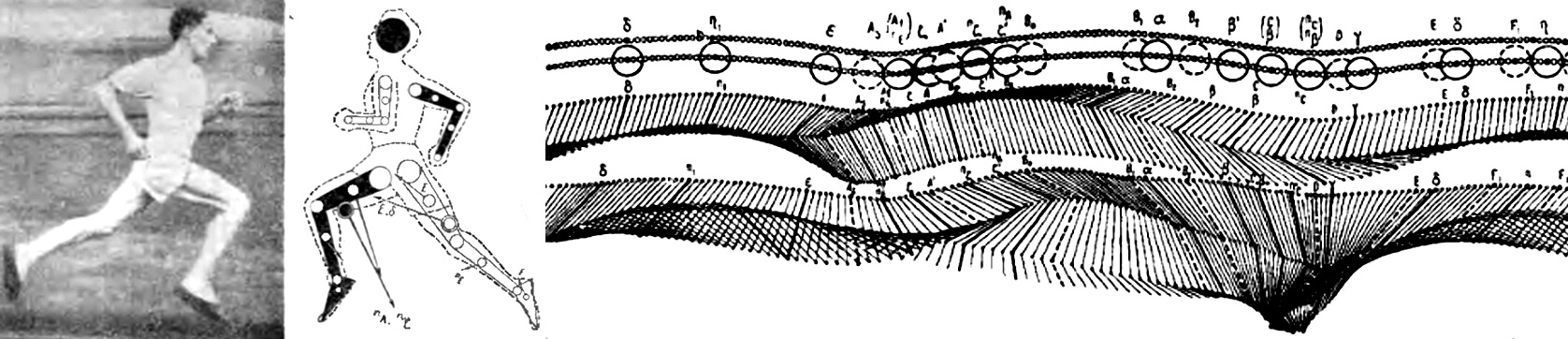

Then we went through, very fast, activities that were complex: juggling, learning dance steps for Hula class, singing, playing the piano and doing gymnastic moves at a super-fast rate. They learned key concepts of improving their coordination that Alexander Technique has to offer for their ability to move freely. Because of having played the Training Game, they could perceive how what they had learned about training themselves could be used in many different situations.

These two girls didn’t have any problem learning abstract concepts in only eight lessons. AND – it was great fun for them!