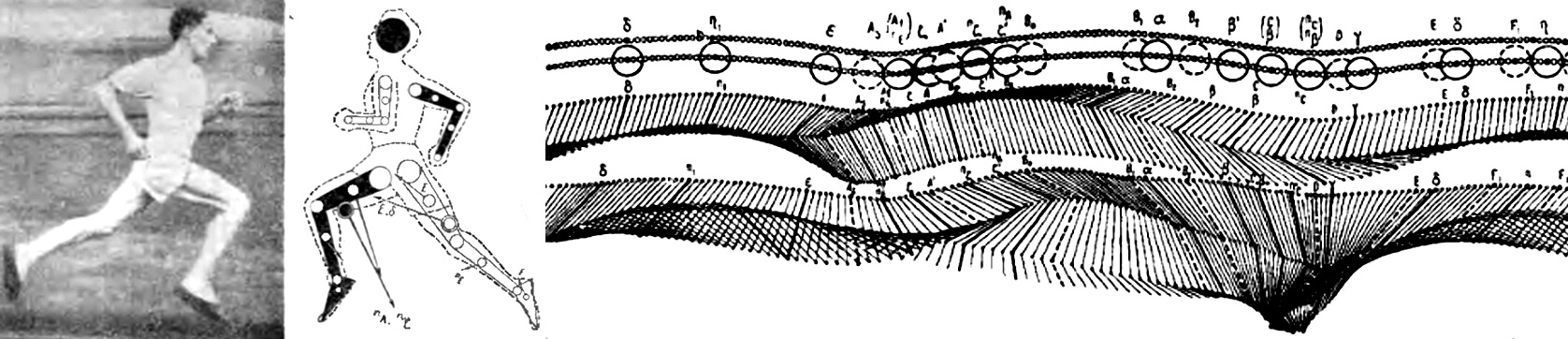

More than a hundred years ago, a Delsartean-inspired actor who figured out how to regain voice loss named F.M. Alexander noticed a principle of human nature related to movement perception and gave it a term: “debauched kinesthesia.”

A more modern term might be: “Sensory Dissonance.” It is what happens when there is a violation of the brain’s “predictive coding” processes that have been described by neuroscience in the Bayesian model of the brain. This model explains how we can instinctively work out whether there is time to cross the road in front of an approaching car or not. We make a prediction based on past experiences, with these predictions (hopefully) updated “on the fly.” Of course, if our “predictive coding” ability doesn’t match reality, our next reaction will depend on how we deal with being wrong. The confounding, irrational quality that a Sensory Dissonant experience seems to possess is related to points described by the terms: Cognitive Dissonance and Cognitive Bias. Denial is most common; (described in *THIS* collection as the “Confirmation Bias”) and accidents can result. If you haven’t read it yet, I have previously outlined in the first half (in the previous post below) the relationship of Sensory Dissonance to these latter categories.

Why Sensory Dissonance Is Important

Aside from avoiding accidents, many more advantages will come from further consideration of this topic. A most interesting area is performance – when you know how to do something, but can’t reliably do it when needed. Or when doing what you imagine you know how to do doesn’t get you where you want to end up.

What most people do about having experienced Sensory Dissonance after making a “mistake,” is to rearrange themselves back to where they believe they “should” be physically oriented. Returning to whatever you sense was the “normal” state of affairs will feel “right” merely because it is most familiar. Because noting your reactions about Sensory Dissonance may also contain an expression of “Cognitive Dissonance” it probably will also be somewhat uncomfortable. (Maybe not; some have learned to welcome and find excitement in what is unfamiliar and unknown.) There’s a payoff of predictable security to resume what is familiar for most people. Most people will be motivated when noting a mismatch to put themselves “right again.”

But should you? But what if your sense of “right” needs calibrating? What if you feel strange when there hasn’t been a kid on your shoulders or you have not done an experiment pushing your arms against a door frame? (Check out the examples in the *first half* of this article.)

When Sensory Dissonance pops into your awareness, there’s an advantage to purposefully allow yourself to feel “strange” and to take a moment to consider what you’re going to do about it. The experience of Sensory Dissonance is an important pointer. This “strange” feedback reveals previously unknown information about the nature of the real state of affairs that would benefit from your thoughtful consideration of what to do about it. It’s an opportunity, don’t ignore it!

Perceptual dissonance is a signal that something different from the norm has just happened. You have the option to act on having noticed a difference by taking the reins back from habitual routines. This calls for using some awareness, strategic thinking and perhaps serious study to revise the affected routines. Perceptual dissonance gives you valuable feedback about what you have been overdoing that might be unnecessary. Viva la difference!

It would be really crazy if every time you carried a weight for awhile, you wanted to put the weight back on again to avoid feeling Sensory Dissonance. But this is the understandable urge in certain situations.

An example: while swimming. Getting back into the water where it feels relatively “warmer” seems logical when the wind factor on skin makes you feel cold in comparison…until your submerged body temperature really drops to match the temperature of the water. Chattering from the cold, you pretty quickly realize that getting back in the water to “get warm” is a short-sighted solution. However, there are many other situations that don’t offer this obvious feedback of mistakenly having made that short-sighted choice!

Act Wisely on Sensory Dissonance

Next time you feel disoriented, consider what this means. Here is a potential for an insight. Maybe pause and consider what you’d like to do about having received a curious sensation of perceptual dissonance, instead of ignoring it and getting yourself back to where you “feel right.”

By deliberately experimenting with Sensory Dissonance, you’ll realize that human sensory orientation judgment is relative, not absolutely “True.”

For instance, if you often stand with your weight on the ball of your foot or on one foot and something gets you to stand with your weight on your heels or both feet, Sensory Dissonance will make you feel strange as if you are leaning backwards or to the “wrong” side. (Women who routinely wear high heels and walk mostly on the ball of their feet know this sensation.) Getting back into those high heels to feel “normal” or transferring all your weight to the other foot is like getting back into the pool to get warm – a short-sighted solution. But in this situation, there is no feedback like getting cold if you stay in the water to tell you that you chose wrong, (unless your feet or calves eventually start hurting or your knees start crumbling.)

What Sensory Dissonance Is Really Telling You

What you might want to do is to think a bit about the important information that Sensory Dissonance is offering you. It’s really saying that your habitual “normal” has been violated. Did you know you were actively doing something in the opposite direction of what Sensory Dissonance just revealed to you? You didn’t until now. Because of the Sensory Dissonance signal, you now have the option of taking the reins back from your habit by using some awareness and strategic thinking to consider changing some of those habits.

The actor quoted at the beginning of the article has solutions. His “Alexander Technique” method always contain this Sensory Dissonant signal that something different has happened. An Alexander Technique teacher gives experiences in classes and “hands-on guided modeling” that reliably feel as if something mysterious and lighter has happened to your movement coordination. It’s the only answer I know about for sifting out problematic features from previously ingrained habits “on the fly,” addressing performance issues involving postural mannerisms.

Hope this little article will lead you to question what you should do about it when you feel Sensory Dissonance. Surprising dissonant sensations can be used as important pointers to bring to your attention that what you just did, felt or experienced. What just happened was something entirely, originally new and different – for you. Here is something that could benefit from your serious attention and consideration – and maybe even be worth investing in long-term study of Alexander Technique!