Alexander Technique is taught using a combination of principles from a few fields of education and some experiments with de-training excessive force. These include…

- how to gain a cumulative benefit through the ways practicing works,

- how to update installation of flexible habits,

- the use of positive reinforcement training,

- some knowledge about living anatomy inside oneself,

- psychological cognitive bias and the nature of assumptions,

- the use of reason,

- mindfulness

- the nature of perception and how it can lead to mistakes

- and some features of neuroscience.

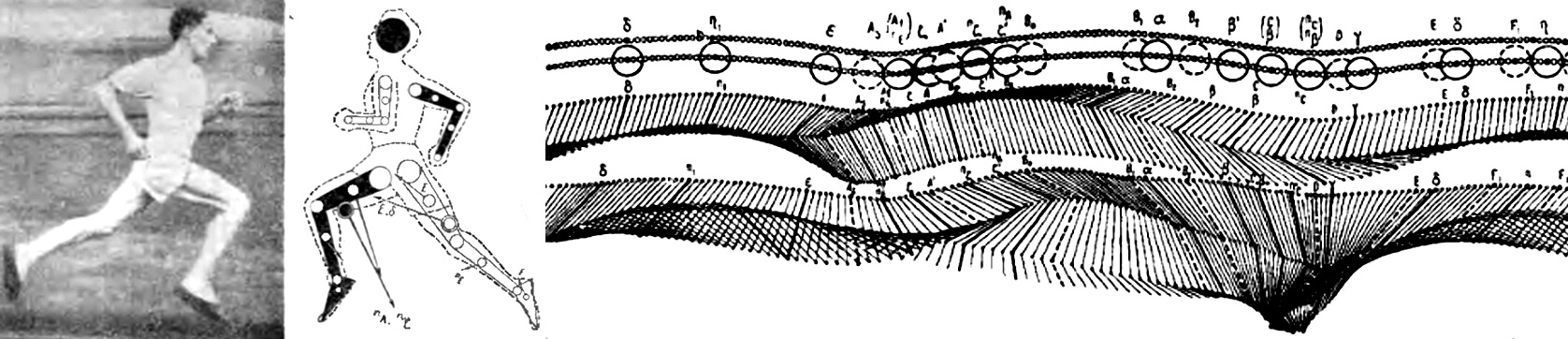

A.T shows how perception of the effects of our intentions work and how habituation can innocently deceive our judgment of “required” effort. (Illustrated by the experiment below, if you’d like to try it.)

All of this back story is designed to be put into action when we do anything we’d like to improve, learn about, do easier or feel better while doing.

Experimenting along the lines of A.T. principles shows us how to undo what we don’t want or need, and how mere subtraction of what we don’t need to do improves success.

Using Alexander Technique results in discoveries, epiphanies, insights and the release of “talent” in more effective practice. (Oh, and using A.T. can change your consciousness. A.T. often has its learners using mindfulness and slowing during practice. That benefit of being able to change your state of consciousness by using Alexander Technique is what makes it “mystique.”)

Now one thing I do know is that…experience is a better teacher than explanations. So try this! It’s a simple experiment that will make you feel some interesting sensations.

…Then think about my explanation of what happens, why it happens and how you can make it happen again.

Find a narrow door, (or a person standing next to you while you stand against a wall that leaves around eight inches away from either side of you when standing.) Stand inside the doorway, (or flanked by the person with the wall on the other side of you.) With the back of your hands, palms inward, push outward and count to 30 seconds. (One one thousand, Two one thousand, etc.) After you count to thirty that way, walk away from the doorway and wave your arms around.

Your arms will feel light as if your arms are rising by themselves!

Before you put your own explanation on what just happened, read ahead and entertain my explanation based on Alexander’s Technique principles. Every physics theory has an experiment to illustrate it’s function in facts. This little experiment shows Alexander’s principle of relative effort disappearing from habituation. (Termed by F.M. Alexander as “debauched kinesthesia.”)

In our experiment, you applied force long enough to temporarily “get used to it,” (only 30 seconds!) then you stopped that force. So you experienced the lack of force needed to move your arms as effortlessness.

I’m trying to sell you on the value of effortlessness!

This odd “weightless” sensation is an indicator that you’ve changed something – that’s our kinesthetic sense of effort, our “sixth sense” which also includes the relative orientation of our body. We’re registering comparative feedback, (not factual sensory feedback, as most people assume.)

It is this relative feedback you’ll learn to spot when you’re using and experimenting with motion – facts about effortlessness is what Alexander Technique offers.

This sensation will tell you you have undone cumulative, collected unnecessary effort. This sensation of effortlessness offers proof that something different happened. This sensation of weightlessness will only occur when there’s a change in how much effort you have applied. You can prove that “relative” nature to yourself also – do the experiment again, and your arms will register less of a change has happened. Now you’re learning to habituate the results of what you did. Repetition causes habituation of what used to be new.

Adaptation is designed to roll new experiences into the background so you can add more new things on top of what you just did while you’re learning what’s known as a “behavior chain” of events that will all link together into being a reliable skill.

Now, imagine the default: Because you do whatever force you usually do all the time habitually, you don’t realize you’re applying whatever force you’re using, even if it is “excessive force.” You’re only registering “customary effort.” This assumption of how much physical effort certain goals are “supposed to take” is inside of every movement you make, because you’ve trained it together with the actions. A certain “background effort” exists in the multitude of things you “normally” do.

…Unless you can move easily without excessive background tension, compared to most people, (this capacity to move easily, as if you were a toddler, is maybe present in one in a thousand adults where I live. It’s high because many people study activities in disciplines that improve effortlessness such as hula, or martial arts such as Aikido or being a “paniolo” which is a Hawaiian cowboy. In mainland American culture, it’s one in every five thousand who never gave up their natural, effortless coordination…according to my own observational ability.) Most people I see around me have justified the existence of cumulative tension that they’ve become completely unaware of using.

Imagine you’re “most people.” Let’s believe that what you’re using to move is force that you’re probably not aware of using. Imagine if you could stop applying this extra force, given how it probably doesn’t contain the benefits you want – selectively? It would make your whole body feel as you did when your arms were…floating.

How can you stop that specific, unnecessary force when you can’t even perceive it? This sense of sharpening relative effort is elusive, because it’s designed to be sensitive to learning new things. Usually you’d only be motivated to change if this excessive force has become so exaggerated so as to cause health issues such as high blood pressure, RSI, or apparently self-imposed limitations that stop you from bettering a beloved skill.

That’s that skill – the skill of learning effortlessness – that Alexander Technique answers!

Alexander Technique can make that extra unnecessary stress disappear, making whatever you’re intending to be doing easier to perform.

You may know better, but imagine if you could actually do that “better,” in spite of a life of mistakes, privations and punishments.

Does that sound interesting?

If you want to read further, here’s another post with more examples:

https://myhalfof.wordpress.com/2015/05/19/sensory-dissonance/

ball in a glance. Otherwise, juggling would not be possible.

ball in a glance. Otherwise, juggling would not be possible.